Bill’s speech to the memorial meeting for Rae Hunter

22 June 1992

The news this morning was that 112 African men, women

and children have died violently in the past week in the latest massacres

in South Africa. With our loss, we can understand the grief in the township

of Boipatong.

But much more; with the convictions that motivated Rae throughout her

life, we understand and must share the anger of these African people

at the conspiracy of De Klerk to brutally prevent their freedom. Rae

knew the suffering of the black African population. She had grown up

in South Africa, and support for African freedom was long a purpose

of her life.

This was the face of imperialism and capitalism. Bush

displayed it when he ushered in his new order in the Middle East with

the annihilation of tens and tens of thousands of Iraqi conscripts and

Arab refugees fleeing the battle zone along the road to Basra, and buried

others alive in the trenches.

Rae, not only wept over the massacres of African people and of Kurds

and Arabs, but was an active enemy of imperialism and a protagonist

of workers' internationalism for over half a century.

Yesterday, a comrade asked me how it was that Rae, after over fifty years, was expressing her ideas and taking action with the same freshness of conviction that she must have had when she first joined the socialist movement.

She had, as everyone bears witness, not a trace of scepticism. And this, in a period when scepticism, cynicism, and self seeking is the hall mark of the right in the labour movement internationally, and, together with paralysis, is a disease of some of the so-called left in the Labour party.

Here, I don't think I gave a full answer to the comrade's

question. There were, of course, Rae’s individual characteristics

but I don’t think they are the decisive answer.

Perhaps Rae's nature, which many comrades have described - for example,

the ability to see the swan in an ugly duckling, played a role, but

the key for her development, the tenacity in the long struggle, rests

in the circumstances at the end of the thirties and beginning of the

forties.

There was a great deal of courage in Rae. More in some ways than I can claim. I can tell a story to help me get through this speech. Rae had open-heart surgery in 1978 after she had been very ill. The surgeon had promised he would phone me immediately after the operation. I got a phone call but it was earlier than I expected. It was a phone call from Rae who was speaking as she was being taken to the operating room. She said: "Hello Bill. I'm just about to have my pre-med. Now I've phoned the boys to keep in touch with you. Don't worry. You will be alright!"

You can, of course, look at Rae's nature. The courage I've spoken about. She never made a mean or malicious remark or committed a personally vindictive act. I think it's absolutely true of her that she left no personal enemies - any enemies she had would be political. There was this objectivity.

I think there was more than that. I think it was also the way she came into the movement, the circumstances of the time and the fact the she was compelled to struggle; but above all her complete dedication to a socialist advance of humanity.

Rae's sister introduced her to Trotskyism which she saw as many people here saw at one time in their lives, as like a blinding light upon the burning questions of the day. She was possessed of a desire to change the world, which was expressed, for her, not just in an academic way, but in actions.

She joined the movement at the end of 1937. She was then a nurse in Paddington, London. She saw, in that area, in that hospital result of poverty and slum conditions. She has discussed her experiences in the hospital with people here; the conditions of patients and nurses, an appalling proportion of whom used to contract tuberculosis at that time. Paddington was an area where, the most fashionable shops and wealthy residential districts together with poverty-stricken districts with terrible housing conditions. The contrasts affected deeply this sensitive middle class girl brought up in the seclusion of a parsonage. And this was in a period when the world was heading rapidly for the Second World War.

At this time, a large number of sensitive young people felt keenly the two great problems of war and fascism. Like a number of the youth who joined the Trotskyist movement, her course toward it went through a pacifist rejection of war.

The problems came before young people then as very sharp problems of life and death as the world lined up for the Second World War. Rae's sister introduced her to Trotskyism which she saw as many people here saw at one time in their lives, like a blinding light upon the questions of the day.

She was possessed of a desire to change the world, which was expressed, for her, not just in an academic way, but in actions. She fought her way into the Trotskyist group.

Right from the beginning, the group, which was known as the Workers International League, formed by people who many of you know or have heard of - such as Jock Haston, Ted Grant, Millie Lee, Ralph Lee and Gerry Healy - would not allow her to join immediately.

They said that she still showed middle class traits, that she still had traces of religion, and that she would have to prove herself for six months. Rae always said that this was wrong, she did not agree with it. But she always said also, that it didn't do her any harm.

She fought in order to get into the movement. And under

the conditions and her experience she began to see and to accept that

the future rested upon the development of the working class. She began

to understand that the working class was forced willy-nilly, however

tortuously, along the road of reorganising society on socialist lines.

Like most of us among the youth who came to Trotskyism at that time

she was attracted by its conclusion that the crisis of humanity was

the crisis of leadership. Her experiences of struggle and her will at

that time to develop leadership assisted her in understanding this.

She felt like other Trotskyist youth of the time, that in order to develop leadership they had to go to work on the factory floor. She left the hospital and went into an engineering factory. That was a big leap for a middle class girl; it was no different to that made by many other girls who were later conscripted into the factories, but on her part it was conscious.

That leap also made the most militant of people. I worked

for several years as convenor in an aircraft factory during the war

and I have never met a more militant group of women than those who had

been conscripted from homes and offices and plunged into a noisy factory

with smelly oil, dirty conditions and long hours.

So she moves through a decision and a fight to join the movement and

a fight to go into the working class to become a leader. Decisions like

these helped to mould her.

They didn't form a personally aggressive, noisy woman.

They formed a woman who underneath was very, very determined; who moved

steadily along the road she set for herself and in the end did what

she wanted to do.

There's a story about us seeing the doctor because of her refusal to

slow down as she grew older and was diagnosed as having angina. Ricky

went first, then I went. Our doctor was a member of the Labour party

who broke with the Communist Party over Hungary. He was a good friend

of ours although we didn’t agree on some points of politics. He

was one of the first to come round and see me when Rae died.

I said to him, when we were worried about her: "You can't stop

her going out. What do we do? She's stubborn." So he laughed and

I said: "What are you laughing at?"

"Well" he replied, "if I tell some people in Liverpool

that Bill Hunter came to me and said somebody was stubborn, I wonder

what they'd say?" Then he went on:

"That stubbornness is what might be called determination. Now I

could say to her: ‘stay in bed till eleven, go to bed at nine-o-clock,

don't get upset over the state of the world and you may live five or

six years longer.’ But for her, that isn't life."

The conclusions went straight into practice with Rae. The members of the Miners Support group, during the miners' strike would tell you that. We had a big support group and we went round, knocking on doors, discussing and collecting food and money. Everybody was concerned about Rae and would ask at times: "Where is she. Is she all right?"

But Rae would be halfway down the street, knocking on doors before others had started and coming back again and again with her bags full of food.

She was known as the "little blond woman with the

"Workers Press". There's a story that was told at the Liverpool

Trades Council. The Liverpool Trades Council is the oldest Trades Council

in the world. It goes back to 1848.

It used to have very big meetings; eighty or a hundred at its monthly

meetings.

The Executive of the Trades Council called a conference one time. For

some reason it was cancelled and postponed to another date but not all

the delegates were informed.

There was an inquest at the Trades Council meeting. In the middle of a heated complaint at not being informed, one delegate said: "I came here, but I knew there was no meeting on when I got to the door, because Rae Hunter was not there with the "Workers Press"”.

The idea went into practice, with Rae. The fight for

socialism was not an academic thing for her, it was very concrete.

Rae had no trace of cynicism. And this is in a period when scepticism,

cynicism, self-seeking is a mark of the right wing in the Labour Movement

and the so-called democratic demagogues in the Soviet Union, and exists,

together with paralysis, among many sections of the left wing now.

We will build a different movement to that; but not a different movement in the principles; not a different movement in the conceptions and ideas that attracted her, and held her.

She was an internationalist. That is why, without hesitation she went with me to Argentina in 1989. And she felt at home there, her only regret was that she never mastered the language to be able to participate as fully in their struggles as she would have wanted.

To the end of her life, she had confidence that the working

class revolution throughout the world would emancipate humanity. She

was confident they would reach the heights of creating a powerful International.

She was born in the year that the Russian Revolution took place. She

died at the time of a very complex and contradictory picture in Eastern

Europe and the Soviet Union. But she knew that the final question of

the victory of capitalism had not been answered there yet and that the

workers had not yet really spoken.

Once again, she was convinced, that material circumstances were driving the working class to a struggle against a restorationist bureaucracy and imperialism. They had, in her conclusion, no other way to go.

The conclusion that she grasped at the end of the thirties was that the working class had all the capacities to fight for socialism and the crisis of humanity lay in the crisis of working class leadership. That conclusion, continually reinvigorated by her experience of struggle remained with her to the end of her life. And the firmness with which she grasped it, gave her a continuous freshness in fighting for it.

We celebrate her life. It is hard, as I know. You don't remove grief by an act of will. The conclusion she grasped all her life and kept her moving with the same fervour, was that the working class had all the potential to fight for socialism.

That conclusion, reinvigorated again and again by struggle,

remained with her to the end of her life. In her last weeks she was

reading a new book on the Spanish Revolution. She was reading the documents

of the struggle; the accounts of POUM members; of Trotskyists. Again

she was attracted by the upsurge of workers and she also felt that they

would rise again in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

The working class has not really spoken yet. Rae felt that. The firmness

with which she grasped those principles which brought her into the movement

gave her that freshness in her struggle and argument for them till the

end of her life.

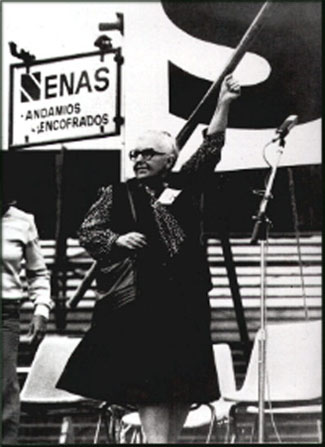

Pictures:

Rae in Argentina

Peter Kerrigan

|

|